Do you speak Klingon – even just a few words? If you don't know what we mean, Klingon is the language commissioned by Paramount Pictures for use in Star Trek. Its structure and rules were invented by a linguist – that is to say, it's a real language. Klingon is so prevalently-spoken among its aficionados that they notice errors if the language is used incorrectly in non-Star Trek realms. But would a Klingon grammar violation, or any use of the language at all, cross a legal-ownership boundary? Does a language invented for commercial purposes preclude its use, or misuse, by others?

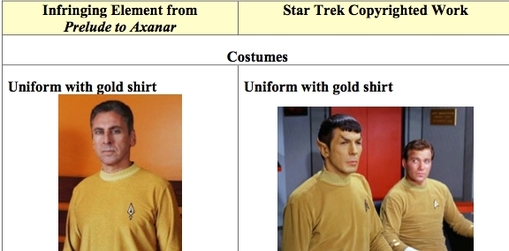

This Klingon murky legalese came up last month when Paramount Pictures sued Axanar Productions, the company behind a crowd-funded Star Trek film. Several sites reported on this issue because the film reportedly uses the pre-existing Star Trek theme, complete with characters sporting the Star-Trek classic mustard-yellow shirts, as well as one character whose ears were shaped a la Dr. Spock's signature physical feature, the pointy Vulcan type. What with the same language, dress, and a unusual body part, on the whole, the indie film wreaks of possible infringement. And that's why Paramount sued.

Leaving the ear shape and the shirt design aside, the Klingon language presents a particular quandary of determining who claims ownership. Disparities abound: In fact, the Klingon Language Institute and the Klingon Wiki state different claims. The former carries a disclaimer that Klingon is a copyright of Paramount. The latter, by contrast, cites the March 2016 Axanar lawsuit, indicating that Paramount claims copyright on Klingon, but does not necessarily possess it. Because Klingon is a language, its ownership nuances are governed differently than, say, Vulcan ears associated with a particular fictional character. Words of a language are considered facts, and facts are not owned, and therefore not copyrightable.

At the same time, the question of language-ownership for Hollywood fiction is small beans in comparison with its potential effect on society at large – on computer programming languages. As a few thought leaders have pointed out, the prime example is the current ongoing trial between Oracle and Google, where Oracle claims Google infringed by using an API written in the Oracle-invented Javascript for the Google-owned Android OS. The initial suit was in 2010, was shot down in 2012, reversed in 2014, denied a Supreme Court certiorari petition, and now has a follow-up $9.6B (yes, that's billion) suit scheduled for this coming May. While we won't get into the details of the case here, suffice it to say there is a fine line between using a language and using a product – in this case an API - in that language.

Intellectual property straddles the tightrope between available, free, general knowledge and patentable product. Within this, language propriety rests partly in the rope's strands, and partly in the world's citizens' waters below. This issue will be far-reaching in our hi-tech world.

This Klingon murky legalese came up last month when Paramount Pictures sued Axanar Productions, the company behind a crowd-funded Star Trek film. Several sites reported on this issue because the film reportedly uses the pre-existing Star Trek theme, complete with characters sporting the Star-Trek classic mustard-yellow shirts, as well as one character whose ears were shaped a la Dr. Spock's signature physical feature, the pointy Vulcan type. What with the same language, dress, and a unusual body part, on the whole, the indie film wreaks of possible infringement. And that's why Paramount sued.

Leaving the ear shape and the shirt design aside, the Klingon language presents a particular quandary of determining who claims ownership. Disparities abound: In fact, the Klingon Language Institute and the Klingon Wiki state different claims. The former carries a disclaimer that Klingon is a copyright of Paramount. The latter, by contrast, cites the March 2016 Axanar lawsuit, indicating that Paramount claims copyright on Klingon, but does not necessarily possess it. Because Klingon is a language, its ownership nuances are governed differently than, say, Vulcan ears associated with a particular fictional character. Words of a language are considered facts, and facts are not owned, and therefore not copyrightable.

At the same time, the question of language-ownership for Hollywood fiction is small beans in comparison with its potential effect on society at large – on computer programming languages. As a few thought leaders have pointed out, the prime example is the current ongoing trial between Oracle and Google, where Oracle claims Google infringed by using an API written in the Oracle-invented Javascript for the Google-owned Android OS. The initial suit was in 2010, was shot down in 2012, reversed in 2014, denied a Supreme Court certiorari petition, and now has a follow-up $9.6B (yes, that's billion) suit scheduled for this coming May. While we won't get into the details of the case here, suffice it to say there is a fine line between using a language and using a product – in this case an API - in that language.

Intellectual property straddles the tightrope between available, free, general knowledge and patentable product. Within this, language propriety rests partly in the rope's strands, and partly in the world's citizens' waters below. This issue will be far-reaching in our hi-tech world.